My weekend began with a visit from my new Canadian friend, "Dan," (see my November 16 post), who brought me the latest issue of New Africa, a magazine based out of Ghana and England. I set it on my coffee table without noticing the cover article about Britain's celebration of the 200th anniversary of Parliament's abolition of the British slave trade, and Dan and I set off for Movie Night, an evening of free outdoor movies sponsored by the senior class.

My weekend began with a visit from my new Canadian friend, "Dan," (see my November 16 post), who brought me the latest issue of New Africa, a magazine based out of Ghana and England. I set it on my coffee table without noticing the cover article about Britain's celebration of the 200th anniversary of Parliament's abolition of the British slave trade, and Dan and I set off for Movie Night, an evening of free outdoor movies sponsored by the senior class.First movie: Ratatouille. Thoroughly enjoyable. Get's my vote for the best animation and story since Finding Nemo.

Second movie: Amazing Grace. This historical drama is a class act from begining to end: well-written, brilliantly acted, and (most amazing of all) historically accurate in, I believe, every significant detail. The story is that of William Wilberforce's leadership of the abolitionist movement in 18th-century England. I had looked forward to the film because of the subject matter (as you may know, I spent two years researching Wilberforce's abolitionist strategy as the subject of my master's thesis), but was unprepared for its extraordinarily high quality as cinema.

The film's only major flaw is a sin of omission rather than commission. Whereas, in the US, the terms "abolition" and "emancipation" are typically used synonymously to refer to the end of slavery, in British parlance, "abolition" refers merely to ending the slave trade--the buying and selling of slaves. This was accomplished in 1807, and this is where, fairly enough, the film ends. The uninitiated American viewer might assume this abolition simultaneously ended British slavery itself, and nothing in the film serves to prevent or correct that assumption--not even the end notes which say that Wilbeforce went on to challenge and change additional aspects of British culture and life.

But Wilbeforce and his colleagues had to fight another 25 years before finally securing emancipation for the millions of slaves still owned by British subjects. This they finally achieved in 1833, just days after Wilberforce's death. (Wilberforce, age 73, had retired by this time, and died happy, assured that the emancipation bill would pass.)

This blurring of abolition and emancipation also mars the issue of New Africa Dan had brought me. The cover article, "Lies, Lies, Lies!," tells of a new book by a British historian who claims, apparently with detailed documentation, that Britain's bicentennial celebration of Abolition is a bunch of self-congratulatory hooey; that Britain continued to build its empire on the products of slave labor late into the 1800s. The book's author and the article's author both are scandalized by this revelation, and the latter heaps calumnies on the Brits, going so far as to wonder if Wilberforce himself were a racist.

The late hour and lack of library resources (or even my thesis and the notes it was based on) prevent a detailed or footnoted response. Suffice it to say:

(1) The main proponents of slavery were those who were benefitting financially from plantation produce (shippers, merchants, bankers, etc.). They spent 20 years fighting abolition because major portions of the economy, and their own profits, were based on slavery. Why would anyone expect them to suddenly forgo the financial benefits they could still milk from the industry, even if they were prevented from the direct sale and purchase of slaves? It's one thing go be scandalized by this. Slavery is scandalous. But, given the historical context, to be surprised by it seems naive.

(2) As pointed out earlier, 1807 marked the legislative end of the British slave trade. It did not mark the end of the slave trade still conducted under the laws of other nations (or of the illegal trade still conducted by some Britons). And it did not end slavery itself, even in Britain and its territories. The slaving industry marched on, denying basic human rights to Africans. And the foodstuffs and other salable items produced by slaves continued to be a huge portion of the British and world economy of the time. Again, what is the surprise here?

(3) Though the article does acknowledge Africans' complicity in the slave trade, the author downplays it, saving his indignation for the British alone (apparently feeling the British are self-serving in their celebration of Wilberforce and Abolition; but isn't it worth commemorating?).

(4) Wilberforce would not have spent over 40 years of his life trying to free British slaves if he were an anti-African racist (the term is anachronistic). To imply such a thing only indicates lack of knowledge of Wilberforce's writings, his life's work, and his reputation among opponents as (to use another anachronism) a "nigger lover."

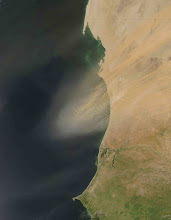

Photo shows a contemporary painting, by John Rising, of Wilberforce at age 29, near the beginning of his abolitionist efforts. Image in the public domain. Downloaded from http://www.hullcc.gov.uk.